The Long and Sexist History of Endometriosis

|

Time to read 11 min

|

Time to read 11 min

In people with endometriosis, tissue similar to the endometrium (the tissue that lines the uterus) grows outside the uterus. Even though this tissue is outside the uterus, it bleeds and tries to shed each month, just like the uterine lining. This process causes widespread inflammation, damages the healthy tissue surrounding the diseased tissue, and over time can lead to scar tissue buildup called adhesions.

While some people who have endometriosis don’t have symptoms, but many have symptoms like:

For some, these symptoms are mild and annoying. For others, these symptoms are so severe they can’t have a normal life.

Unfortunately, as Dr. Allyson Shrikhande, the Chief Medical Officer of Pelvic Rehabilitation Medicine, explains,

“Endometriosis research remains underfunded and understudied despite affecting 1 in 9 women*, essentially millions of women worldwide. Many doctors still lack proper training in diagnosing and treating the disease. The slow progress in finding better treatments and understanding its causes reflects a gender bias in medical research, where women’s health issues receive less attention and funding.”

It seems wild that a disease that impacts one in nine people assigned female at birth (AFAB) is still so misunderstood in 2025. But it makes more sense when you look back on the long history of sexism in medicine and how it tainted the diagnosis and treatment of menstrual disorders.

So, let’s take a journey through medical history to see how endometriosis has been identified and diagnosed throughout the centuries.

Table of Contents

None of the ancient medical literature that’s survived can prove that Ancient Greek and Roman doctors encountered endometriosis because the disease can only be officially diagnosed when doctors literally see the diseased tissue during surgery. But nationally renowned endometriosis experts Drs. Camran Nezhat, Farr Nezhat, and Ceana Nezhat, all believe that Greco-Roman doctors treated endometriosis regularly based on their analysis of medical texts dating back to the 5th century B.C.E.

Several of these texts describe a disease with all the symptoms of endometriosis –

Some also described “adhesions between the uterus and other parts” and “ulcers,” which sounds a lot like the diseased tissue and lesions caused by endometriosis.

Medical texts written by Arab, Asian, European, and Muslim physicians in the 5th through 10th centuries described a similar disease. So, it seems like ancient doctors all over the world were observing the same disease.

The same medical literature also reveals that sexism surrounding menstrual disorders is as old as the medical profession. Greco-Roman doctors believed that abnormal menstrual cycles and all the symptoms that accompanied them were caused by an “animalistic womb” that was “hungry for motherhood” as the Drs. Nezhat put it in their research. This belief spawned the idea that a uterus without a fetus could become “displaced” and “wander” around the body. Shockingly, this remained the commonly accepted cause of menstrual disorders through the 19th century! So, the official medical perspective on menstrual disorders went something like this: if a woman didn’t fulfill her duty of getting pregnant on a regular basis, her uterus malfunctioned.

Sadly, echoes of this can still be found in modern medicine. A 2023 study published in BMC Women's Health found that 89% of women with endometriosis were told by a healthcare professional that pregnancy can treat endometriosis, even though this is completely untrue.

As the world entered the Middle Ages, the explanations for menstrual disorders evolved, but somehow got even more sexist. Medical texts from this era written by physicians all over the world explained that menstrual disorders were caused by “suffocation” or “strangulation” of the uterus. Though the idea that the uterus can be strangled or suffocated is obviously ridiculous, these terms might have been a primitive way of describing the intense, painful uterine contractions that cause cramps and heavy bleeding in people with endometriosis.

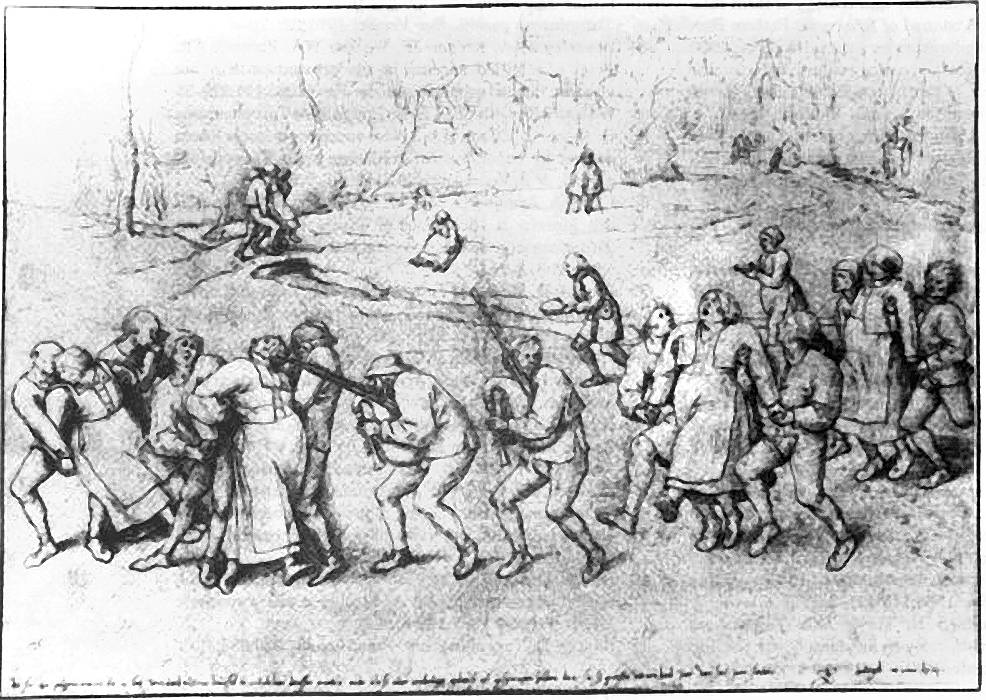

Many Medieval physicians believed that only promiscuous women and women who used primitive forms of birth control suffered from “suffocation” or “strangulation” of the uterus. Believing that these immoral women deserved harsh treatment for their menstrual disorders, doctors often suggested shouting at the uterus and choking women so their “wandering uterus” would return to the correct place (seriously, what?!?). Other doctors believed that menstrual disorders were the result of demonic possession, so they prescribed exorcisms.

Despite the era’s extremely sexist and hyper-religious perspectives, physicians in the Middle Ages did make some important discoveries, mostly because autopsies became more mainstream. As they were performed on women who’d been treated for pelvic pain and excessive menstrual bleeding, physicians found that many of these women had lesions, adhesions, and inflammation throughout the pelvic cavity. Medical texts from the Middle Ages also include the first theories that linked recurrent pelvic pain to the menstrual cycle, reports of patients experiencing pelvic pain so intense that they actually lost consciousness, and documented cases of “ulcers” in the uterus .

Because of these findings, physicians began to believe that menstrual disorders could either cause or be caused by damage to the uterus. Imagine that! *Big eye roll*

Though medicine made incredible advancements in the 16th through 18th centuries, societal attitudes toward women, the explosion of the study of psychology, and a resurgence of religious fervor made things even worse for women struggling with menstrual disorders. While physicians were studying diseases with chronic, recurrent symptoms that aligned with the menstrual cycle and gathering evidence that abnormal menstruation had a physical cause, psychologists and religious zealots were pushing the theory that symptoms related to the menstrual cycle were a psychological disease (hysteria) or a spiritual disease (witchcraft).

Hysteria was a psychological diagnosis given to women who had physical symptoms doctors couldn’t explain. Since the majority of doctors didn’t know, or care to know, much about women’s bodies, women experiencing symptoms triggered by their menstrual cycles were often diagnosed with hysteria. They were told that their symptoms didn’t exist because they were sick, they existed because they were crazy.

After examining the medical literature about women diagnosed with hysteria, some contemporary endometriosis specialists believe that many of these women were actually suffering from endometriosis.

The misdiagnosis of legitimate menstrual disorders as hysteria has irrevocably influenced how women and people assigned female at birth get treated by physicians and the medical system.

As Dr. Shrikhande, explains, “Medical theories such as ‘hysteria,’ ‘wandering womb,’ and ‘suffocating womb’ suggested that women’s ailments were rooted in emotional instability or a malfunctioning uterus rather than real physiological conditions. These pseudo-diagnoses contributed to the dismissal of endometriosis symptoms, delaying accurate medical recognition and treatment. Women with chronic pelvic pain were often referred to psychiatry or psychiatric institutions to address their emotional instability rather than the disease process itself.”

The diagnosis of hysteria also stalled research into menstrual disorders.

“The belief that menstrual pain and pelvic disorders were primarily psychological led to a lack of medical urgency in studying endometriosis,” Dr. Shrikhande says. “Many women were told their pain was normal, stress-induced, or a result of their emotional state, discouraging research into effective treatments.”

Luckily, some physicians did continue to look for physical causes for the recurring, persistent symptoms their patients experienced with their monthly cycles.

Physicians in 17th century France described lesions and adhesions similar to those caused by endometriosis. Around the same time, German physician Daniel Schrön used an early version of a microscope to examine the lesions and adhesions found on the uteri of patients with menstrual disorders, and identified that tissue very similar to the endometrium could grow outside the uterus.

Related Articles

→ Why Does Endometriosis Cause Pain During Sex

Surgical advances in the early 19th century led to multiple breakthroughs in the diagnosis and treatment of menstrual disorders. As doctors performed abdominal surgeries on women to treat various issues, they discovered that some of their patients had abnormal tissue growing outside the uterus and throughout the pelvic cavity. They also noted that this tissue appeared to cause lesions, adhesions, and significant inflammation.

One of these surgeons, Carl Rokitansky , wrote what’s widely recognized as the first pathological report on endometriosis. By the mid-1800s Rokitansky also reported that the uterine-like tissue could grow and damage tissue on the ovaries.

In the late 1800s, Dr. Thomas Cullen became one of the first physicians to examine the uterine-like tissue found outside the uteri of women with menstrual disorders under a modern microscope. This analysis confirmed that this tissue was nearly identical to the endometrium, and Cullen concluded that the abnormal tissue growth and the lesions and inflammation it caused were a previously unidentified disease.

A gynecologist named John Sampson finally named that previously unidentified disease endometriosis in 1921. His extensive research, mostly conducted by examining tissue samples taken during surgical procedures, led to the first comprehensive description of endometriosis as a unique disease as well as the discovery of endometriomas, also known as chocolate cysts.

Physicians also focused on developing surgical treatments for endometriosis during this time period. Dilation and curettage (D&C) was a popular treatment option in the late 1800s and early 1900s. During the same time period, surgeons started performing the first endometriosis excision surgeries. Unfortunately, the fatality rate for these surgical procedures was as high as 50%.

Alas, sexism was still rampant among 19th and early 20th century physicians treating menstrual disorders. Even though research showed that symptoms associated with menstruation often had a real, physical cause, women who reported symptoms directly associated with their periods were still more likely to be given a psychological diagnosis than a medical one. Because endometriosis was almost exclusively diagnosed in older women back then, physicians believed the disease didn’t exist in younger women. So, they went undiagnosed.

Because physicians often associated pelvic pain exclusively with sexually transmitted infections, women reporting pelvic pain were often misdiagnosed with STIs and shamed for being promiscuous. These attitudes didn’t even begin to shift until the 20th century, and as anyone who’s been to a bad (often male) doctor knows, they still haven’t shifted enough.

You’ve heard of the clitoral hood, now get ready for the clitoral hoodie. Inspired by how far more time and research has gone into understanding outer space than human vulvas—oh, and Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (get a load of those shells!).

With the Venus Hoodie, you can publicly express:

All profits from the gold Venus Sweatshirt will be donated to Endo Black in honor of Endometriosis Awareness Month :)

Research into endometriosis exploded in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. Physicians studying it discovered that the uterine-like tissue that defined endometriosis could grow outside of the pelvic cavity, and soon identified that it could grow anywhere in the body. Terrifying, right?

During the 1940s, surgeons refined procedures to treat endometriosis. Advancements in surgical equipment and techniques made it possible to perform endometriosis excision surgery through multiple small incisions (laparoscopic surgery) instead of one large abdominal incision (laparotomy).

Around the same time, surgeons discovered that the abnormal tissue unique to endometriosis could actually grow in surgical scars, including the surgeries that were supposed to treat endometriosis. Unfortunately, this discovery made many doctors nervous about using surgery to treat endometriosis, and many stopped recommending it for their patients.

In the 1950s, doctors experimented with using high dose estrogen to treat endometriosis, but the side effects were too severe. Luckily, the birth control pill was released in 1957. Since the birth control pill combined estrogen and progestin, there were fewer side effects, and women could use them continuously to stop their periods, which eliminated many of their endometriosis-related symptoms.

Research into hormonal treatments for endometriosis continued over the next two decades. In the 1970s, Danazol became the first medication specifically approved by the FDA for the treatment of endometriosis. However, because it was a testosterone-based medication, long term use could lead to facial hair growth, voice changes, and enlargement of the clitoris. So, most women chose not to use Danazol.

For the next few decades, research into endometriosis slowed because hormonal interventions seemed to manage most patients’ symptoms. Surgery was only recommended for patients with the most severe cases of endometriosis.

However, further research into endometriosis, especially in patients who didn’t respond well to hormonal treatment, revealed that hormone therapy doesn’t actually stop the progression of endometriosis . It can slow the growth of the abnormal tissue, and it often provides significant symptom relief, but the disease still progresses.

In light of this information, many endometriosis specialists now recommend laparoscopic excision surgery for endometriosis patients whose quality of life is impacted by their symptoms, even if it doesn’t seem like their disease is severe.

Though the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis has massively improved in the past few decades, the sexism surrounding the disease has not.

Dr. Shrikhande says, “Women with endometriosis often wait 6-8 years for a proper diagnosis. Many doctors dismiss their pain, prescribing birth control or opioid painkillers rather than investigating further. Racial and socioeconomic disparities also play a role, with women of color and lower-income women facing even greater barriers to diagnosis and treatment.”

But it doesn’t have to be this way. There are doctors out there who will listen to you and believe what you have to say about your pain. There are medical professionals out there who will work with you to diagnose and treat pelvic pain, and determine whether endometriosis could be the cause. And there are treatments out there that can provide significant relief.

Endometriosis has been around for thousands of years

Endometriosis was commonly misdiagnosed as hysteria, witchcraft, and nymphomania for centuries

Historical treatments for endometriosis ran the gamut—from leeches to strangulation to exorcisms

We've come a long way since the middle ages, but the sexist history of endometriosis contributes to delayed diagnoses and dismissal of pelvic pain to this day